A Very Special Family Profile

by Aïda Rogers

Reprinted with permission © 1998 Sandlapper

Society.

"When I lost my father, I couldn't understand why that happened.

Family and friends ask why I go to Super Weekend every year. If they

could only see what we have, they'd understand."

Dewayne Crite

1994 James F. Byrnes scholar

This story is to help them understand

Photo by Richard Durlach: Judge Bobby Mallard of Charleston,

1959 Byrnes scholar, shares a laugh at the scholar's June luncheon.

Somewhere in the dim mists of my college years, I remember hearing

about Byrnes scholars. The girl I shared a bathroom with was one. Bootsie

was quiet. It was her roommate Ann who told me her father had died

years ago. Somehow I made the connection that Bootsie had her scholarship

because she didn’t have a father. I also knew she had a friend

outside our Capstone 18th floor circle, a girl named Henri, who also

was a Byrnes scholar. In my young, self- absorbed way, I never thought

more about it.

"Where’s Boots?" I remember asking Ann. "At one

of those Byrnes things," Ann would say. I still feel my face puzzling,

and I still see Ann shrugging. For us – both parents alive, from

households where college was so expected it wasn’t even discussed – we

just didn’t understand.

Later, when I was at my first "real" job in North Myrtle

Beach, Bootsie came to visit. It was a Sunday afternoon, and she had

just left the Byrnes Super Weekend in Garden City. I don’t remember

what we talked about, but it wasn’t Super Weekend. She probably

knew it wouldn’t sink in.

But now it has. I’ve been baptized by the Byrnes Family. I made

it through a Super Weekend and was feted at the June luncheon. I’ve

sung

"Carolina Moon" and played crazy games at the beach. After

lots of conversations, I may know more about The Byrnes Foundation

and the miracle man who started it than some of the 900 people who’ve

won scholarships since 1949.

It’s a great story. I hope you read it.

I don't know where I would be without my Byrnes scholarship

Photo

by Richard Durlach: 1996 scholars Jennifer Brigman (left)

and Laura Whitlock at the 1998 June luncheon.

"I don't know where I would be without my Byrnes scholarship,"

says Natalie Owens, an '86 scholar from Columbia. It's a frequently

heard comment at Super Weekend, the annual gathering that draws current

and alumni scholars to Chapel by the Sea in Garden City. It's here

where an outsider can become an insider; indeed, spouses and children

have been making the pilgrimage since 1964, when Super Weekend was

started. It's a nod to the first "super weekend" of 1951,

when Gov. James F. Byrnes took about 90 of his scholars to his home

at Isle of Palms. Those scholars are pushing 70 today, but they still

remember the chocolate ice cream cones, the Coast Guard boat trips

and the limousine rides.

They also remember visiting him and his wife Maude at the governor's

home - the unassuming Byrnes disliked the word "mansion" -

and singing around the piano with them. To them, Byrnes was a beloved

benefactor who made possible the thing he always wanted but never had:

a college education. Through the foundation he established in 1948,

he was able to award scholarships to students like himself - academically

gifted, community-minded and financially needy. There were only two

other qualifications: Recipients had to be from South Carolina, and

one or both parents had to be dead. It's painful to be a Byrnes scholar.

Byrnes made the most of what he had. His father died before he was

born, and his mother, a seamstress, taught him shorthand. He parlayed

that skill into court reporting, which later led to reading the law.

Though he quit school at 14, he became a newspaper editor, lawyer,

solicitor, congressman, senator and governor. While in Washington,

he was appointed Supreme Court justice, secretary of state and

"assistant president" to FDR during the crucial World War

II years. When he came back to South Carolina in 1949, he began his

dearest project: He started a family.

And what a family it is. Byrnes events are noisy affairs, full of

hugging and kissing, laughing and crying. Scattered now across the

country,

"brothers" and "sisters" range from 18 to 67; they're

black, white, Asian, married, divorced, single, pregnant, parents,

grandparents. Young men with earrings and ponytails are "brothers" to

men who could be their grandfathers. Alumni children, or "Byrnes

grandkids," are clucked over and scolded; they're friends with

each other.

There's even some inbreeding. Not too many years ago, a "sister"

married a "brother" - something Byrnes always wanted. Board

member Dal Poston, a 1974 scholar from Taylors, started the trend by

marrying the daughter of long-time executive secretary Margaret Courtney.

Years later, he introduced his uncle to Nancy Norton Drew, a 1959 scholar,

board secretary and sister to Rev. Hal Norton, a 1949 scholar and board

president. Now that Nancy Norton Drew has married Dal Poston's uncle,

three Byrnes scholars are metaphorical double first-cousins. "We

fish in the same stream," Hal Norton deadpans, before turning

serious. "Relationships are begun here, but they're very deep

relationships. Dal and I are more than friends, We aren't blood kin,

but we're kin, and that's the way it is for a lot of people here."

And so it is. Scholars graduate and remain friends; they vacation

together and put each other up when they're passing through town. Younger

scholars consult older ones for advice - which the older scholars did

with Byrnes himself. Henri Duncan of Columbia and Johnna Edmunds of

Clover, both 1979 scholars, are roommates now in Columbia. "Once

a Byrnes scholar, always a Byrnes scholar," observes Dr. Bill

Rowe, a 1949 scholar and board treasurer. He, like many alumni, speculate

they became the children Maude and Jimmy Byrnes never had.

"Mom and Pop Byrnes wanted the scholarship to be more than just

a check," Rowe upholds. In truth, scholars are practically forced

to bond. Current scholars are required to attend Super Weekend in March,

the annual June luncheon in Columbia and fall dinners near their colleges

with local alumni scholars.

Likewise, they must submit to a family tradition or two - like the

singing of "Carolina Moon" and "Let Me Call You Sweetheart,"

Byrnes' favorite songs. If Maude and Jimmy Byrnes wanted a family,

they got it: Twenty-six years after his death, those scholars are still

singing.

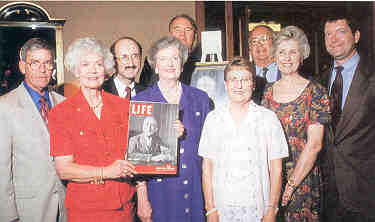

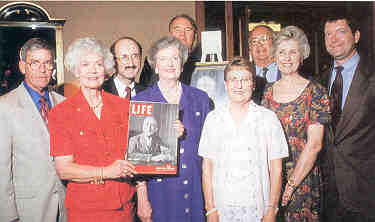

We're family

Photo by Richard Durlach: The James F. Byrnes Foundation

Board of Directors – (from left) Dr. Bill Rowe, Lois Anderson,

Charles Wall, Carol Ann Green, Dal Poston (behind), Jeanette Cothran,

Rev. Hal Norton (behind), Nancy Drew Poston, Deaver McGraw III.

Bill Rowe and Dolly Wells are reminiscing at Dianne's on Devine, a

popular Columbia restaurant, Thursday before the Saturday June luncheon.

Rowe is a surgeon in Chattanooga; Wells is an education specialist

at the SC Department of Archives and History. They're grandparents

now, but almost 50 years ago, they were USC students and among the

first Byrnes scholars. They've been so close for so long that it's

natural for Wells to dab her napkin at something on Rowe's cheek. "We're

family," she explains.

Rowe is the oldest Byrnes scholar, a fact gleefully and frequently

noted by Hal Norton, who is four days younger. Rowe may also be the

most concerned of the scholars that Byrnes hasn't been adequately remembered

by history. Hence his talks about Byrnes at Super Weekend and his collection

of newspaper clippings, magazine articles, photos and books about the

statesman. It was Byrnes' two autobiographies, .Speaking Frankly and

All in One Lifetime, that provided the first $100,000 for his scholarship

foundation, Byrnes' well-heeled friends (Bernard Baruch, among others)

also pitched in. Later, Byrnes would sell his Isle of Palms home to

keep the foundation running.

For her part, Wells is sorry that younger scholars never met The Man.

"They try to understand, but there's no way. Unless you experience

him in his aura, you couldn't know him." Wells describes Byrnes

as a serious person who was concerned about his state and country,

but who nevertheless loved a good time and. young people. Short, with

a penchant for double-breasted suits and top hats and an aversion to

people who were late and those who didn't try, Byrnes was everything

you'd want in. a parent: warm, compassionate, funny and loving. Though

she stayed more in the background, Maude Byrnes still made speeches

for her husband and was just as well-loved by the scholars. Older scholars

still talk about. how comfortable. And accessible they were.

For many, it was a mutual adoption. Rowe., a Georgetown native and

ROTC student, sought Byrnes' advice about whether his medical school

plans would be jeopardized. by entering the Navy during the. Korean

War. Wells, a 1961 scholar and "double orphan" from Charleston.

consulted Byrnes about politics. Wells also talked to them both about

marrying before her senior year, which then meant sacrificing the scholarship.

It was a difficult decision, but they were supportive.

"They were always encouraging, and they wanted you to do what

you thought was best for yourself," she recalls. "They believed

in self-reliance and independence and they believed in us."

Besides providing loving attention and. a college education, Byrnes

tried to create citizens of the world, Wells says. "That's what

all this was about. He did not want us to have a narrow focus in life.

He wanted us to branch out and be internationally knowledgeable and

to become involved ourselves."

Byrnes engaged many of his Washington colleagues to speak at the June

luncheons. As always, he involved the scholars, asking one to "read

up" on the speaker and introduce him at the assembly. Speakers

included generals Mark Clark, William Westmoreland and Lucious Clay;

United Nations official Porter McKever; Roger Peace; Sen. Strom Thurmond;

and Gov. Donald Russell, Byrnes' law partner and first president of

the foundation. Who wouldn't be impressed and inspired?

"He expected you to try," Wells says. "He instilled

a sense of wanting to improve yourself and to be of some service."

Surely this man had a flaw. "No," Wells says immediately.

Adds Rowe: "We don't think so."

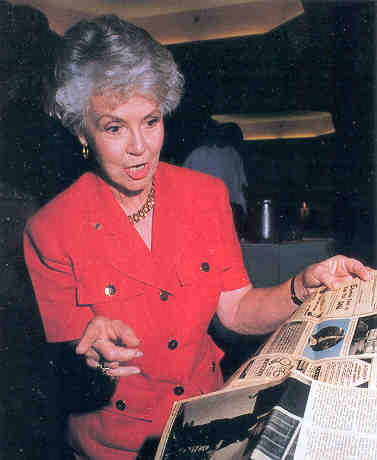

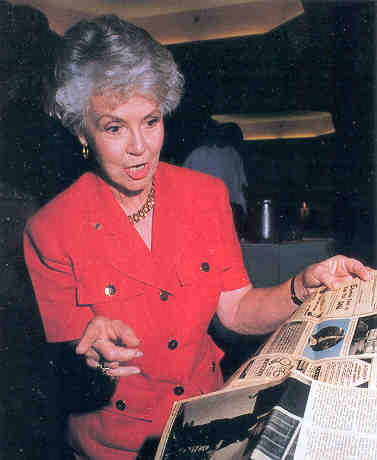

As the result of an education

Photo by Richard Durlach: Lois Hatfield Anderson, Class of

1950, shows off treasures from "Mom" Byrnes' sewing basket.

"Punctuality is something you absolutely must, must, must respect," preaches

Lois Anderson to a room of scholars at Super Weekend.

"Respond, respond, respond, respond, respond," she emphasizes

minutes later about the meaning of RSVP.

Anderson remembers when she was Lois Hatfield, intimidated by wealth,

uncertain about table manners. Her hour-long etiquette class has become

a Super Weekend staple, with some alumni scholars sitting in to refresh

themselves on social graces.

On the agenda are tips for shaking hands - "Don't crunch their

bones and don't give them the dead fish" - and the skinny on hats: "You

guys need to know that if you are socially correct, the hat has to

go. I don't let anybody sit at my table with a hat on, and that you

can call archaic if you want to."

Proper use of answering machines, how to deal with cherry tomatoes,

what to do with your napkin when you're finished eating, the necessity

of thank-you notes and the unacceptability of obscenities are covered

by Anderson, a Lee County native and Coker College graduate. Too well

she remembers her jitters in 1950, when she met the Byrnes for the

first time at their Spartanburg home. Armed with pointers from a helpful

teacher - "start at the outside of your silver and work your way

in, and watch your hostess" - she was relieved to be greeted by

a lunch on paper plates with wooden spoons. "It was wonderful," she

recalls.

The Byrnes were wonderful, and the scholarship changed her life, says

Anderson, a former teacher. "It's given me a greater appreciation

for what a little old country girl can learn and be as a result of

an education. It's an absolute fact I could never have gone to college

had it not been for the Byrnes scholarship. I was a half orphan when

I got it, I was a full orphan when I finished with it, and there was

just no way!"

Anderson treasures Maude Byrnes' sewing basket, filled with receipts,

programs and drafts of notes. The Byrnes were exemplary role models.

She tries to pass on through her etiquette classes some of what she's

been taught.

"It is important that you know what to do when you go somewhere

that's going to have an influence on the rest of your life," she

sums up. As class is dismissed, she tells the students to call any

time with questions - collect, she adds quickly.

They understand the best

Photo

courtesy Becky Roach. "I was trying to snap a photo of

Mom and Pop Byrnes, and he said, 'I'll give you something to photograph.'

With that, he reached over, grabbed her, and gave her a big kiss. There's

no doubt who either was singing about when they sang 'Let Me Call You

Sweetheart.'"

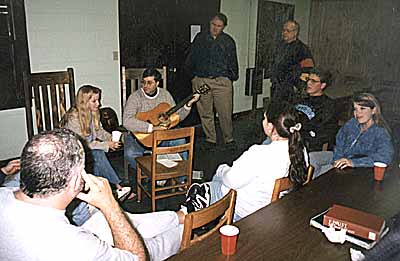

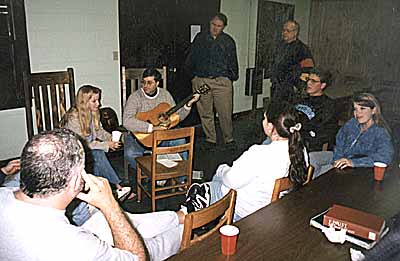

Photo courtesy of Allen Easler: Ron Cobb, with guitar,

leads a group of scholars in a late-night Super Weekend singalong.

"Frankly, I feel like a little of a schmuck for having been away

for so long," Ron Cobb, 36, is saying. He's just finished the

final event of Super Weekend: a seafood buffet lunch in Murrells Inlet

followed by the traditional singing of "On Top of Old Smoky," which

is usually led by Judge Bobby Mallard, a 1959 scholar from Charleston.

Cobb, a Gaffney native, has been picking up degrees from Wake Forest

and Princeton since he graduated from Furman in 1984; he's missed only

two Super Weekends in 18 years. Now he's in Boston, working on a Ph.D.

in clinical psychology, and getting married soon. Like others who take "the

family" seriously, he's brought his fiancée. She needs

to pass inspection.

"It's important to me that she feel at home in this family because

I don't want to be pulled away from this group," Cobb explains. "It's

an important relationship for me and I don't want to lose it."

Some spouses haven't been interested in the Byrnes family, and eventually

those scholars lose touch, he says. But Cobb brought fiancée

Jan Weathers to meet his family in Gaffney last year. That same week,

he brought her to Super Weekend. "This is the best weekend of

my year, and the good thing is I get to do it every year," he

says.

Cobb is a favorite at Saturday night's talent show, where he plays

guitar and sings funny songs by Mike Cross. The regulars sing along

with the choruses, and children sit on their parents' laps, swinging

their legs and clapping. For Cobb, an admitted introvert whose father

died when he was 17, performing proves how emotionally helpful his

scholarship was. "I needed to be with people who understood, and

I also needed a group I could give back to," he reflects. "Knowing

myself, I may have never talked things over with people who had also

been through this kind of pain."

For Cobb, it was especially important to come to Super Weekend 1998.

His sister recently died. "This is the time I want to be with

this family the most, because they understand the best."

Ditto, says Mark Matlock, a Greenville newspaper editor whose wife

Elaine, a 1976 scholar, died two years ago. Matlock has brought 9-year-old

daughter Rachel to Super Weekend to soak up the support. "I told

my family about it, how wonderful it was, but they really got a first-hand

look at the Byrnes scholars at Elaine's funeral," he remembers. "It

seemed like every other person that came up said, 'I'm a Byrnes scholar

and I heard about Elaine.' My dad said, 'Boy, they just come out of

the woodwork, don't they?'"

Meanwhile, Ron Cobb wants to come back home. "When I think about

settling someplace for the rest of my life, it's because of the Byrnes

family. I want to play a role in the foundation and carry on the tradition.

That needs to survive."

The rumbly voiced Hal Norton - sometimes solemn, most times jovial

- maneuvers Super Weekend from opening barbecue to seafood finale.

The most emotional moments come Saturday night, when graduating seniors

are invited to talk. Some thank the board for being chosen; others

get teary. One young man challenges other seniors not to "toss

this aside." Emily Tingle, a summa cum laude senior at

Presbyterian College who'll teach English in China next year, has this

to say: "Our sorrow is turned to joy and I just want to thank

you for that."

Norton looks over the room and delivers the ultimate compliment. "If

someone were looking for a son or daughter, they could come here, but

they'd have a problem. They wouldn't know which one to take."

This exhausted reporter over-sleeps Sunday, missing breakfast. But

she scrambles to worship services. At its conclusion, board member

and "family photographer" Charles Wall gives instructions

for the official Super Weekend photo. There's a lot of laughing as

Wall explains how to line up so every face can be seen. And then we're

off, everyone carrying a chair to the lodge where the picture will

be taken.

I lumber with them, notebook under one arm, chair under the other.

I'm just planning to watch all the wiggling as Wall does his thing.

But Deaver McCraw, Easley computer consultant and '78 scholar, is walking

beside me. "You're going to be in the picture, aren't you? You're

part of the family now."

Too surprised to say anything, I take my place with the rest. Two

little girls are sitting in front of me, an older man stands to my

right, McCraw on my left. We smile for the camera. This picture is

a keeper.